Impulsarse y Caminar

Description

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

The momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$) can be expressed as a set of its different components:

$\vec{p}=(p_x,p_y,p_z)$

Its derivative can be expressed as the derivative of each of its components, so with:

| $ F =\displaystyle\frac{ dp }{ dt }$ |

we obtain, by differentiating with respect to the time ($t$), that

$\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}\vec{p}=\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(p_x,p_y,p_z)=\left(\displaystyle\frac{dp_x}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dp_y}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dp_z}{dt}\right)=(F_x,F_y,F_z)=\vec{F}$

which allows us to determine the force ($\vec{F}$):

| $\vec{F}=\displaystyle\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}$ |

(ID 3239)

As the relationship with the action force ($F_A$) and the reaction force ($F_R$) in one dimension is

| $ F_R =- F_A $ |

it can be applied to each component of the action force (vector) ($\vec{F}_A$) and the reaction force (vector) ($\vec{F}_R$), resulting in

$\vec{F}R=(F{Rx},F_{Ry},F_{Rz})=(-F_{Ax},-F_{Ay},-F_{Az})=-\vec{F}_A$

hence

| $ \vec{F}_R = - \vec{F}_A $ |

(ID 3240)

As the magnitude of torque is

| $ T = r F $ |

If the axis unit vector is

$\hat{n}=\hat{r}\times\hat{t}$

Therefore, considering

$\vec{F} =F\hat{t}$

,

$\vec{r} =r\hat{r}$

,

$\vec{T}=T\hat{n}$

we have

$\vec{T} =T\hat{n}=T\hat{r}\times\hat{t}=rF\hat{r}\times\hat{t}=\vec{r}\times\vec{F}$

which means

| $ \vec{T} = \vec{r} \times \vec{F} $ |

(ID 3249)

In the case of a balance, a gravitational force acts on each arm, generating a torque

| $ T = r F $ |

If the lengths of the arms are $d_i$ and the forces are $F_i$ with $i=1,2$, the equilibrium condition requires that the sum of the torques be zero:

| $\displaystyle\sum_i \vec{T}_i=0$ |

Therefore, considering that the sign of each torque depends on the direction in which it induces rotation,

$d_1F_1-d_2F_2=0$

which results in

| $ d_1 F_1 = d_2 F_2 $ |

.

(ID 3250)

(ID 3251)

Con la definici n de torque medio:

| $ T_m =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta L }{ \Delta t }$ |

\\n\\nse puede pasar al limite instant neo en la medida que se consideren tiempos infinitesimales

$T\equiv \lim_{t\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{\Delta L}{\Delta t}\equiv \displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}$

con lo que el torque instantaneo se define con la derivada del momento angular:

| $ T =\displaystyle\frac{d L }{d t }$ |

(ID 3252)

Since the moment is equal to

| $ L = I \omega $ |

it follows that in the case where the moment of inertia doesn't change with time,

$T=\displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}=\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(I\omega) = I\displaystyle\frac{d\omega}{dt} = I\alpha$

which implies that

| $ T = I \alpha $ |

.

(ID 3253)

As a vector can be expressed as an array of its different components

$\vec{a}=(a_x,a_y,a_z)$

its derivative can be expressed as the derivative of each of its components

$m_i\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}\vec{a}=m_i\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(a_x,a_y,a_z)=\left(m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_x}{dt},m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_y}{dt},m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_z}{dt}\right)=(F_x,F_y,F_z)=\vec{F}$

Therefore, in general, the instantaneous velocity in more than one dimension is

| $ \vec{F} = m_i \vec{a} $ |

(ID 3598)

If the moment ($p$) is defined with the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$) as

| $ p = m_i v $ |

This relationship can be generalized for more than one dimension. In this sense, if we define the vector of the velocidad de las partículas (vector) ($\vec{v}$) and the momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$) as

$\vec{p}=(p_x,p_y,p_z)=(m_iv_x,m_iv_y,m_iv_z)=m_i(v_x,v_y,v_z)=m_i\vec{v}$

then

| $ \vec{p} = m_i \vec{v} $ |

(ID 3599)

(ID 3683)

If we consider the variation of momentum over time $t+\Delta t$ and at $t$ as:

$\Delta p = p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)$

and $\Delta t$ as the elapsed time, then in the limit of infinitesimally small time intervals:

$F_m=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)}{\Delta t}\rightarrow \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{dp}{dt}$

This last expression corresponds to the derivative of the position function $p(t)$:

| $ F =\displaystyle\frac{ dp }{ dt }$ |

which is also the slope of the graph representing that function over time.

(ID 3685)

Si se deriva en el tiempo la relaci n para el momento angular

| $ L = r p $ |

para el caso de que el radio sea constante

$T=\displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}=r\displaystyle\frac{dp}{dt}=rF$

por lo que

| $ T = r F $ |

(ID 4431)

Examples

Momentum is a measure of the quantity of motion that increases with both mass and velocity.

In cases with more dimensions, velocity becomes a vector and thus so does momentum:

| $ \vec{p} = m_i \vec{v} $ |

(ID 3599)

According to Galileo, objects tend to maintain their state of motion, meaning that the momentum

$\vec{p} = m\vec{v}$

should remain constant. If there is any action on the system that affects its motion, it will be associated with a change in momentum. The difference between the initial momentum $\vec{p}_0$ and the final momentum $\vec{p}$ can be expressed as:

| $ dp = p - p_0 $ |

(ID 3683)

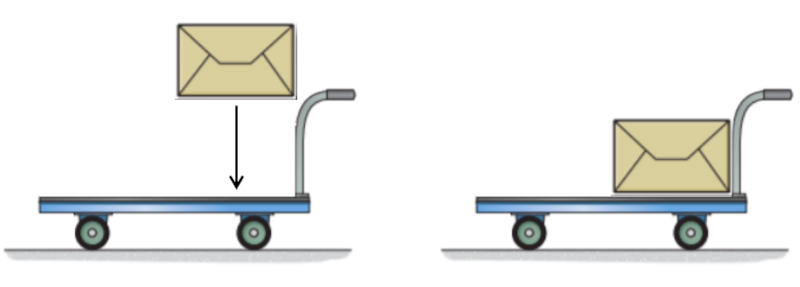

If no force acts on a body, its moment of inertia will remain constant. This means that the product of the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$) will stay constant. In other words, if the mass increases, the velocity will decrease, and vice versa. To understand why this happens, imagine a cart with a certain mass and velocity to which an additional mass is added. This added mass is initially at rest in our system and therefore has no momentum. The cart must transfer some of its momentum to the new mass so that it acquires the same velocity as the cart, resulting in a loss of momentum and a reduction in the cart's speed:

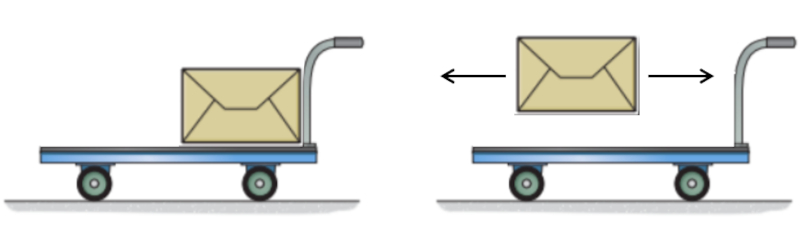

Conversely, if we throw a mass from a moving cart in such a way that the mass comes to a complete stop, we will recover the momentum that the mass had, thereby increasing the cart's momentum and, consequently, its speed. This can only happen if the mass stops when thrown; if it is simply released, it will continue moving at the same velocity.

This last process also helps us understand the third law of action and reaction, as acting on the released mass allows us to harvest the corresponding reaction.

(ID 3238)

In general, the force with constant mass ($F$) should be understood as a three-dimensional vector, that is, the force ($\vec{F}$). This means that the moment ($p$) is described by a vector the momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$). Thus, the expression with the time ($t$):

| $ F =\displaystyle\frac{ dp }{ dt }$ |

is generalized as:

| $\vec{F}=\displaystyle\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}$ |

It's important to note that the force acts in the direction and sense of the variation of the momentum vector over time.

(ID 3239)

The force ($F$) is defined as the momentum variation ($\Delta p$) by the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), which is defined by the relationship:

| $ F \equiv\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta t }$ |

(ID 3684)

The average force is calculated as the change in momentum $\Delta p$ divided by the elapsed time $\Delta t$, using the formula:

| $ F \equiv\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta t }$ |

This formula provides an approximation of the real force, which may become distorted if the force fluctuates during the time interval. Therefore, the concept of an instantaneous force is introduced, which is determined over an infinitesimally small time interval.

| $ F =\displaystyle\frac{ dp }{ dt }$ |

corresponds to the derivative of momentum and represents the instantaneous force.

(ID 3685)

For the case where the inertial Mass ($m_i$) is constant, it also holds true that the force with constant mass ($F$) should be understood as a three-dimensional vector, that is, the force ($\vec{F}$). This implies that the instant acceleration ($a$) is described by a vector the instantaneous acceleration (vector) ($\vec{a}$). Thus, the expression with the force with constant mass ($F$):

| $ F = m_i a $ |

is generalized as:

| $ \vec{F} = m_i \vec{a} $ |

(ID 3598)

The relationship between the action force ($F_A$) and the reaction force ($F_R$) in one dimension:

| $ F_R =- F_A $ |

can be generalized to more dimensions with the action force (vector) ($\vec{F}_A$) and the reaction force (vector) ($\vec{F}_R$), as follows:

| $ \vec{F}_R = - \vec{F}_A $ |

(ID 3240)

The moment ($p$) was defined as the product of the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$), which is equal to:

| $ p = m_i v $ |

The analogue of the speed ($v$) in the case of rotation is the instantaneous Angular Speed ($\omega$), therefore, the equivalent of the moment ($p$) should be a the angular Momentum ($L$) of the form:

| $ L = I \omega $ |

.

the inertial Mass ($m_i$) is associated with the inertia in the translation of a body, so the moment of Inertia ($I$) corresponds to the inertia in the rotation of a body.

(ID 3251)

Si el momento angular se mantiene constante

| $L=L_0$ |

se tiene con

| $ L = I \omega $ |

se tiene que variaciones en el momento de inercia es compensado con variaciones en la velocidad angular

| $ I_1 \omega_1 = I_2 \omega_2 $ |

(ID 3600)

El torque medio calculado con la variaci n del momento angular

| $ T_m =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta L }{ \Delta t }$ |

por ello el torque instantaneo se puede definir en el limite de tiempo infinitesimal:

| $ T =\displaystyle\frac{d L }{d t }$ |

(ID 3252)

In the case where the moment of inertia is constant, the derivative of angular momentum is equal to

| $ L = I \omega $ |

which implies that the torque is equal to

| $ T = I \alpha $ |

This relationship is the equivalent of Newton's second law for rotation instead of translation.

(ID 3253)

Both the first and second laws of Newton apply to rotational motion.

Inertia explains that objects tend to maintain a constant angular velocity while rotating.

Changes in angular momentum over time are associated with torque, which, analogous to force in translation, is what causes rotation.

In the case of the third principle, which associates every action with an equal and opposite reaction:

| $ \vec{F}_R = - \vec{F}_A $ |

in a similar manner, for every applied torque $T_a$ there exists a reaction torque $T_r$ of equal magnitude but opposite direction:

| $ \vec{T}_R =- \vec{T}_A $ |

This physically implies that we always need a pivot point to generate torque so that the system can experience the reaction torque.

(ID 3254)

Since the relationship between angular momentum and torque is

| $ L = r p $ |

its temporal derivative leads us to the torque relationship

| $ T = r F $ |

The body's rotation occurs around an axis in the direction of the torque, which passes through the center of mass.

(ID 4431)

Torque is represented as a vector aligned with the axis of rotation. Because the radius of rotation and the force are orthogonal, the relationship is

| $ T = r F $ |

This can be expressed as the cross product of angular velocity and radius:

| $ \vec{T} = \vec{r} \times \vec{F} $ |

(ID 3249)

If a bar mounted on a point acting as a pivot is subjected to the force 1 ($F_1$) at the force - axis distance (arm) 1 ($d_1$) from the pivot, generating a torque $T_1$, and to the force 2 ($F_2$) at the force - axis distance (arm) 2 ($d_2$) from the pivot, generating a torque $T_2$, it will be in equilibrium if both torques are equal. Therefore, the equilibrium corresponds to the so-called law of the lever, expressed as:

| $ d_1 F_1 = d_2 F_2 $ |

(ID 3250)

ID:(319, 0)