Interior flow and erosion

Storyboard

Internal flow occurs through the capillaries formed between the soil particles. Whenever these capillaries have dimensions greater than those of the small clay plates, there is a risk that these clay particles may be carried away by this flow. If this happens, the soil could lose some of its clay content, which would impact its mechanical properties, stability, and support for organic life.

ID:(379, 0)

Interior flow and erosion

Description

Internal flow occurs through the capillaries formed between the soil particles. Whenever these capillaries have dimensions greater than those of the small clay plates, there is a risk that these clay particles may be carried away by this flow. If this happens, the soil could lose some of its clay content, which would impact its mechanical properties, stability, and support for organic life.

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

Another useful equation is the one corresponding to the conservation of energy, which is applicable in cases where viscosity, a process that leads to energy loss, can be neglected. If we consider the classic energy equation $E$, which takes into account kinetic energy, gravitational potential energy, and an external force displacing the liquid over a distance $\Delta z$, it can be expressed as:

$E=\displaystyle\frac{m}{2}v^2+mgh+F\Delta x$

If we consider the energy within a volume $\Delta x\Delta y\Delta z$, we can replace the mass with:

$m=\rho \Delta x\Delta y\Delta z$

And since pressure is given by:

$F=p \Delta S =p \Delta y\Delta z$

We obtain the equation for energy density:

| $ e =\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v ^2+ \rho g h + p $ |

(ID 3159)

When a the pressure difference ($\Delta p_s$) acts on a section with an area of $\pi R^2$, with the tube radius ($R$) as the curvature radio ($r$), it generates a force represented by:

$\pi r^2 \Delta p$

This force drives the liquid against viscous resistance, given by:

| $ F_v =-2 \pi r \Delta L \eta \displaystyle\frac{ dv }{ dr }$ |

By equating these two forces, we obtain:

$\pi r^2 \Delta p = \eta 2\pi r \Delta L \displaystyle\frac{dv}{dr}$

Which leads to the equation:

$\displaystyle\frac{dv}{dr} = \displaystyle\frac{1}{2\eta}\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta L} r$

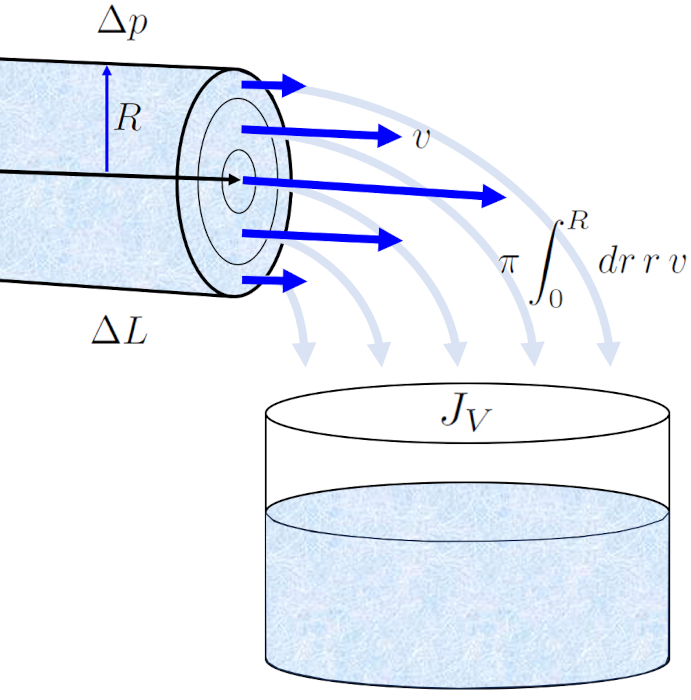

If we integrate this equation from a position defined by the curvature radio ($r$) to the edge where the tube radius ($R$) (taking into account that the velocity at the edge is zero), we can obtain the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) as a function of the curvature radio ($r$):

| $ v = v_{max} \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{ r ^2}{ R ^2}\right)$ |

Where:

| $ v_{max} =-\displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{4 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

is the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$) at the center of the flow.

(ID 3627)

If we assume that the energy density ($e$) is conserved, we can state that for a cell where the average velocity is the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$), the density is the density ($\rho$), the pressure is the water column pressure ($p$), the height is the column height ($h$), and the gravitational acceleration is the gravitational Acceleration ($g$), the following holds:

| $ e =\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v ^2+ \rho g h + p $ |

At point 1, this equation will be equal to the same equation at point 2:

$e(v_1,p_1,h_1)=e(v_2,p_2,h_2)$

where the mean Speed of Fluid in Point 1 ($v_1$), the height or depth 1 ($h_1$), and the pressure in column 1 ($p_1$) represent the velocity, height, and pressure at point 1, respectively, and the mean Speed of Fluid in Point 2 ($v_2$), the height or depth 2 ($h_2$), and the pressure in column 2 ($p_2$) represent the velocity, height, and pressure at point 2, respectively. Therefore, we have:

| $\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v_1 ^2+ \rho g h_1 + p_1 =\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v_2 ^2+ \rho g h_2 + p_2 $ |

(ID 4504)

(ID 4506)

(ID 4507)

In the case where there is no hystrostatic pressure, Bernoulli's law for the density ($\rho$), the pressure in column 1 ($p_1$), the pressure in column 2 ($p_2$), the mean Speed of Fluid in Point 1 ($v_1$) and the mean Speed of Fluid in Point 2 ($v_2$)

| $\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v_1 ^2 + p_1 =\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} \rho v_2 ^2 + p_2 $ |

can be rewritten with the variación de la Presión ($\Delta p$)

| $ dp = p - p_0 $ |

and keeping in mind that

$v_2^2 - v_1^2 = \displaystyle\frac{1}{2}(v_2-v_1)(v_1+v_2)$

with

| $ \bar{v} = \displaystyle\frac{ v_1 + v_2 }{2}$ |

and

| $ \Delta v = v_2 - v_1 $ |

you have to

| $ \Delta p = - \rho \bar{v} \Delta v $ |

(ID 4835)

(ID 10630)

Examples

(ID 1237)

(ID 107)

The profile of the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) in the radius of position in a tube ($r$) allows us to calculate the volume flow ($J_V$) in a tube by integrating over the entire surface, which leads us to the well-known Hagen-Poiseuille law.

The result is an equation that depends on ERROR:5417,0 raised to the fourth power. However, it is crucial to note that this flow profile only holds true in the case of laminar flow.

Thus, from the viscosity ($\eta$), it follows that the volume flow ($J_V$) before ERROR:5430.1 and ERROR:6673.1, the expression:

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

The original papers that gave rise to this law with a combined name were:

![]() "Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in r hrenf rmigen Gef ssen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).

"Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in r hrenf rmigen Gef ssen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).

![]() "Recherches exp rimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de tr s-petits diam tres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Acad mie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

"Recherches exp rimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de tr s-petits diam tres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Acad mie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

(ID 2216)

(ID 1639)

ID:(379, 0)