Heat transport mechanism

Image

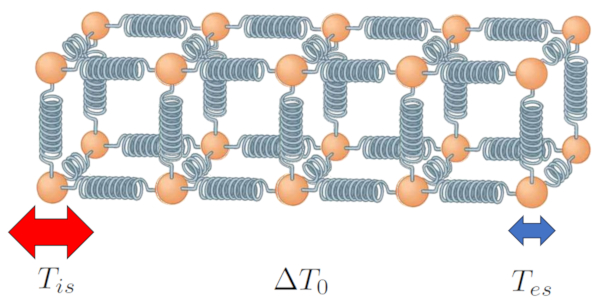

In the case of a solid, and similarly for a liquid, we can describe the system as a structure of atoms held together by something that behaves like a spring. When both ends have temperatures of ERROR:10165.1, with the inner surface temperature ($T_{is}$) and the outer surface temperature ($T_{es}$):

| $ \Delta T_0 = T_{is} - T_{es} $ |

The temperature difference implies that the atoms at the ends oscillate differently; atoms in the high-temperature zone will have a greater amplitude in their oscillations compared to the atoms in the low-temperature zone.

However, this difference will gradually lead to the entire chain oscillating in such a way that, in the end, the amplitude will vary along the path, from the highest values where the temperature is also higher, to the lowest values in the lower-temperature zone.

In this way, the temperature difference in the conductor ($\Delta T_0$) leads to ERROR:10159.1 in ERROR:10160.1.

ID:(15234, 0)

Heat conduction mechanism

Note

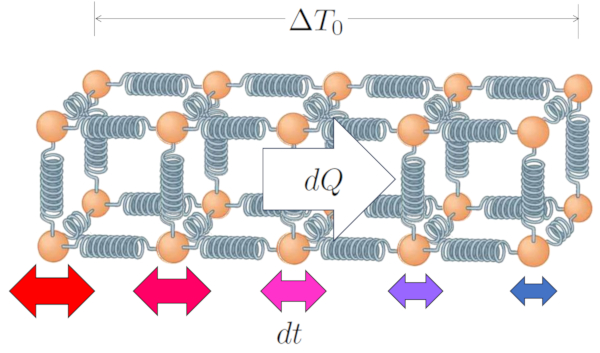

To understand how heat is conducted, you can think of a body as being represented by chains of springs that oscillate according to their temperature. If one end of the body has a higher temperature, the corresponding oscillation will also be greater. Since neighboring components oscillate to a lesser extent, they will be gradually affected, leading to the slow distribution of the oscillation/temperature along the chain, as depicted below:

Conduction will be more effective when there are more chains (cross-sectional area) present, and it will be slower as the chains become longer.

ID:(11188, 0)

Total heat transport by a conductor

Quote

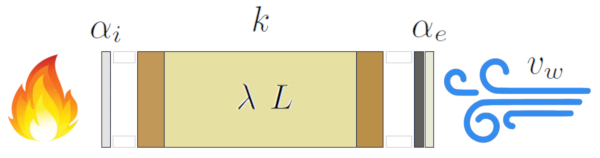

Heat transfer and conduction models suggest that it is possible to develop a relationship that incorporates all three mechanisms together. This equation should take into account the heat transported ($dQ$), the time variation ($dt$), the temperature difference ($\Delta T$), the section ($S$), and the total transport coefficient (multiple medium, two interfaces) ($k$):

Mathematically, this can be expressed as follows:

| $ q = k \Delta T $ |

ID:(15241, 0)

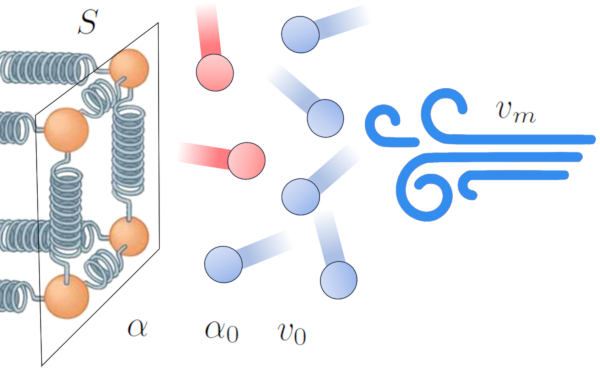

Dependence of the transfer coefficient on the velocity of the medium

Exercise

One of the effects of heat transfer from a conductor to an external medium is the heating of the medium near the interface, creating an interference zone in the transmission. This decreases the efficiency of the transfer and tends to form an insulating layer that reduces the flow of energy.

However, this effect can change in the presence of wind. The wind can remove the layer of high-temperature atoms and molecules, enhancing the efficiency of heat transfer. This suggests that the transmission coefficient ($\alpha$) is influenced by the mean speed ($v_m$) [1,2]:

In this context, we model the relationship based on ERROR:9844,0 and a reference factor of the media reference speed ($v_0$).

The mathematical relationship that describes this phenomenon for a gas with the transmission coefficient in gases, dependent on speed ($\alpha_{gv}$), the mean speed ($v_m$), the transmission coefficient in gases, independent of speed ($\alpha_{g0}$), and the transmission coefficient gas velocity factor ($v_{g0}$) is:

| $ \alpha_{gv} = \alpha_{g0} \left(1+\displaystyle\frac{ v_m }{ v_{g0} }\right)$ |

And for a liquid with the transmission coefficient dependent on the speed ($\alpha_{wv}$), the mean speed ($v_m$), the transmission coefficient Independent of the speed ($\alpha_{w0}$), and the factor velocidad del coefiente de transmisión ($v_{w0}$):

| $ \alpha_{wv} = \alpha_{w0} \left(1+\sqrt{\displaystyle\frac{ v_m }{ v_{w0} }}\right)$ |

This illustrates how wind can significantly influence the efficiency of heat transfer between a conductor and an external medium.

![]() [1] "Über Flüssigkeitsbewegung bei sehr kleiner Reibung" (On Fluid Movement with Very Little Friction), Ludwig Prandtl, 1904

[1] "Über Flüssigkeitsbewegung bei sehr kleiner Reibung" (On Fluid Movement with Very Little Friction), Ludwig Prandtl, 1904

![]() [2] "Die Abhängigkeit der Wärmeübergangszahl von der Rohrlänge" (The Dependence of the Heat Transfer Coefficient on the Length of the Pipe), Wilhelm Nusselt, 1910

[2] "Die Abhängigkeit der Wärmeübergangszahl von der Rohrlänge" (The Dependence of the Heat Transfer Coefficient on the Length of the Pipe), Wilhelm Nusselt, 1910

ID:(3620, 0)

Heat transport mechanisms

Storyboard

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

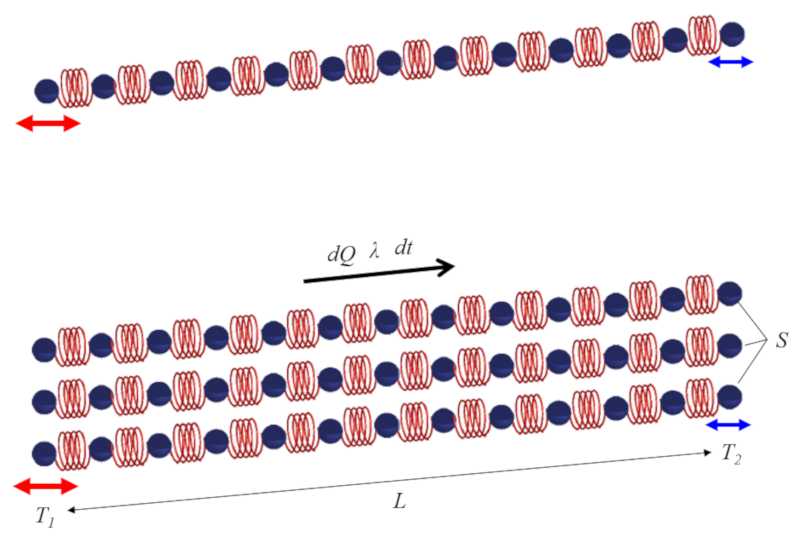

Since the heat transported ($dQ$) is a function of the conductor length ($L$), the section ($S$), the time variation ($dt$), the temperature difference in the conductor ($\Delta T_0$), and the thermal conductivity ($\lambda$) according to the following equation:

With the equation for the heat flow rate ($q$) defined as:

In the infinitesimal case, where the conductor length ($L$) reduces to ERROR:10179.1 and the temperature difference in the conductor ($\Delta T_0$) becomes the temperature variation ($dT$), the equation simplifies to:

The quantity of the heat transported ($dQ$) through ERROR:10179.1 can be calculated using the heat flow rate ($q$) and the time variation ($dt$) with the section ($S$) through the following equation:

$dQ = -\displaystyle\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(q S dt) dz$

Since the heat flow rate ($q$) with the temperature variation ($dT$) and the thermal conductivity ($\lambda$) is defined as:

Therefore,

$dQ = \displaystyle\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\lambda \displaystyle\frac{\partial T}{\partial z}) S dz dt$

On the other hand, we can relate the heat supplied to liquid or solid ($\Delta Q$) with the mass ($M$), the specific heat ($c$), and the temperature variation ($\Delta T$) through the equation:

In this case, with the volume Variation ($\Delta V$), the equation becomes:

$dQ=\rho dV c dT = \rho c S dz dT$

And finally, we have:

Examples

In the case of a solid, and similarly for a liquid, we can describe the system as a structure of atoms held together by something that behaves like a spring. When both ends have temperatures of ERROR:10165.1, with the inner surface temperature ($T_{is}$) and the outer surface temperature ($T_{es}$):

The temperature difference implies that the atoms at the ends oscillate differently; atoms in the high-temperature zone will have a greater amplitude in their oscillations compared to the atoms in the low-temperature zone.

However, this difference will gradually lead to the entire chain oscillating in such a way that, in the end, the amplitude will vary along the path, from the highest values where the temperature is also higher, to the lowest values in the lower-temperature zone.

In this way, the temperature difference in the conductor ($\Delta T_0$) leads to ERROR:10159.1 in ERROR:10160.1.

To understand how heat is conducted, you can think of a body as being represented by chains of springs that oscillate according to their temperature. If one end of the body has a higher temperature, the corresponding oscillation will also be greater. Since neighboring components oscillate to a lesser extent, they will be gradually affected, leading to the slow distribution of the oscillation/temperature along the chain, as depicted below:

Conduction will be more effective when there are more chains (cross-sectional area) present, and it will be slower as the chains become longer.

Heat transfer and conduction models suggest that it is possible to develop a relationship that incorporates all three mechanisms together. This equation should take into account the heat transported ($dQ$), the time variation ($dt$), the temperature difference ($\Delta T$), the section ($S$), and the total transport coefficient (multiple medium, two interfaces) ($k$):

Mathematically, this can be expressed as follows:

One of the effects of heat transfer from a conductor to an external medium is the heating of the medium near the interface, creating an interference zone in the transmission. This decreases the efficiency of the transfer and tends to form an insulating layer that reduces the flow of energy.

However, this effect can change in the presence of wind. The wind can remove the layer of high-temperature atoms and molecules, enhancing the efficiency of heat transfer. This suggests that the transmission coefficient ($\alpha$) is influenced by the mean speed ($v_m$) [1,2]:

In this context, we model the relationship based on ERROR:9844,0 and a reference factor of the media reference speed ($v_0$).

The mathematical relationship that describes this phenomenon for a gas with the transmission coefficient in gases, dependent on speed ($\alpha_{gv}$), the mean speed ($v_m$), the transmission coefficient in gases, independent of speed ($\alpha_{g0}$), and the transmission coefficient gas velocity factor ($v_{g0}$) is:

And for a liquid with the transmission coefficient dependent on the speed ($\alpha_{wv}$), the mean speed ($v_m$), the transmission coefficient Independent of the speed ($\alpha_{w0}$), and the factor velocidad del coefiente de transmisión ($v_{w0}$):

This illustrates how wind can significantly influence the efficiency of heat transfer between a conductor and an external medium.

![]() [1] " ber Fl ssigkeitsbewegung bei sehr kleiner Reibung" (On Fluid Movement with Very Little Friction), Ludwig Prandtl, 1904

[1] " ber Fl ssigkeitsbewegung bei sehr kleiner Reibung" (On Fluid Movement with Very Little Friction), Ludwig Prandtl, 1904

![]() [2] "Die Abh ngigkeit der W rme bergangszahl von der Rohrl nge" (The Dependence of the Heat Transfer Coefficient on the Length of the Pipe), Wilhelm Nusselt, 1910

[2] "Die Abh ngigkeit der W rme bergangszahl von der Rohrl nge" (The Dependence of the Heat Transfer Coefficient on the Length of the Pipe), Wilhelm Nusselt, 1910

For a conductor with values of the conductor length ($L$) and the section ($S$), the flow of the heat transported ($dQ$) is described under the time variation ($dt$) and the thermal conductivity ($\lambda$) as follows:

In the infinitesimal case, where the conductor length ($L$) reduces to ERROR:10179.1 and the temperature difference in the conductor ($\Delta T_0$) becomes the temperature variation ($dT$), the equation for the heat flow rate ($q$) simplifies to:

[1] "Th orie analytique de la chaleur" (The Analytical Theory of Heat), Joseph Fourier, Cambridge University Press (2009) (original 1822)

The heat flow rate ($q$) is defined in terms of the heat transported ($dQ$), the time variation ($dt$), and the section ($S$) as follows:

The definition of the heat flow rate ($q$) is established using the thermal conductivity ($\lambda$) and the temperature variation ($dT$) as a function of the distance traveled ($dz$) through the following equation:

By studying heat flow, we obtain the equation for the absolute temperature ($T$) as a function of the position along an axis ($z$), the time ($t$), and the thermal conductivity ($\lambda$), which becomes the specific heat ($c$). The equation for the density ($\rho$) simplifies to:

ID:(1512, 0)