Water Flow

Storyboard

In saturated soil, there can be situations where pressure variations occur. These variations, in turn, generate flow that, in this case, should occur within the soil pores. Since these pores are on the order of microns or tens of microns, the flow tends to be laminar due to the low Reynolds numbers.

ID:(369, 0)

Flux density solution from a channel

Concept

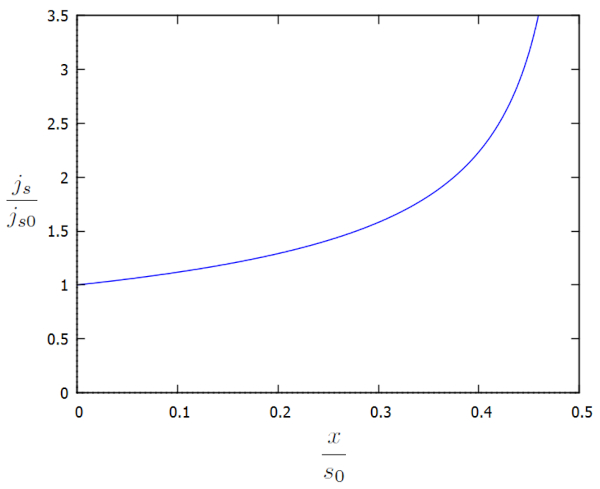

The solution obtained for the height and the parameters the flow at a reference point ($j_{s0}$) and the reference height of the water column ($h_0$) shows us that the flux density ($j_s$) is equal to:

| $ \displaystyle\frac{ j_s }{ j_{s0} } = \displaystyle\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \displaystyle\frac{ 2 x }{ s_0 }}} $ |

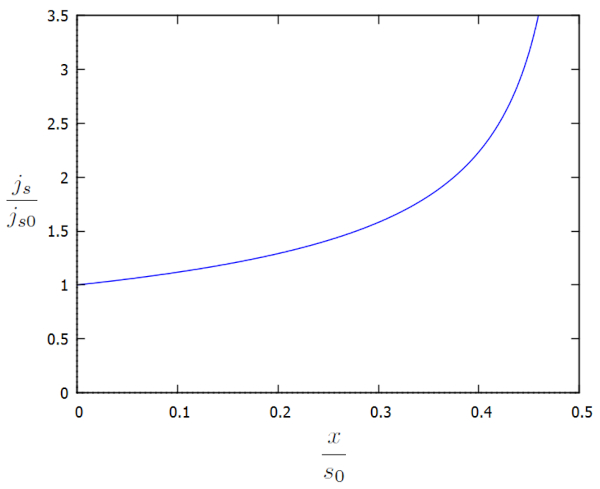

We can graphically represent the flux density ($j_s$) in terms of the additional factors $j_s/j_{s0}$ and $x/x_0$ as follows:

the flux density ($j_s$) continues to increase as we approach the channel, as the height of the water column on the ground ($h$) decreases. This increase is necessary to maintain the flow velocity in the flux density ($j_s$) or, alternatively, to increase it.

ID:(7827, 0)

Laminar flow through a tube

Concept

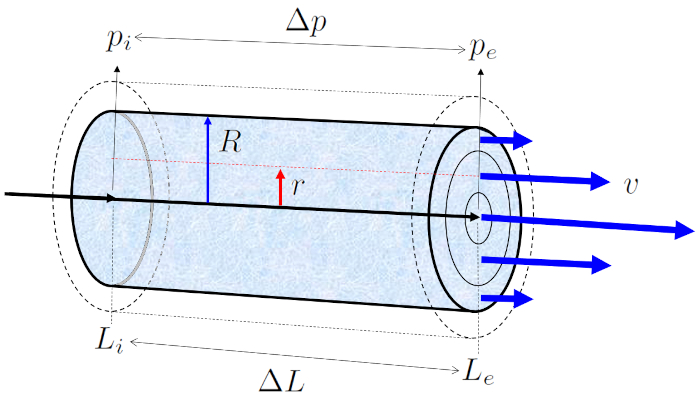

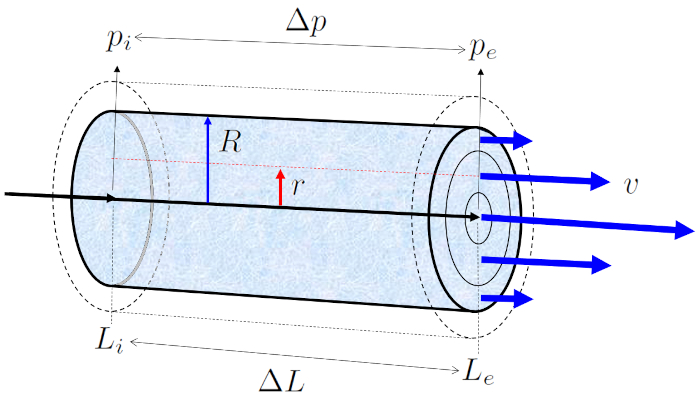

When a tube filled with liquid with a viscosity of ERROR:5422,0 is exposed to the pressure in the initial position ($p_i$) at the position at the beginning of the tube ($L_i$) and the pressure in end position (e) ($p_e$) at the position at the end of the tube ($L_e$), it generates a pressure difference ($\Delta p_s$) along the tube length ($\Delta L$), resulting in the profile of the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$):

In flows with low values of the number of Reynold ($Re$), where viscosity is more significant than the inertia of the liquid, the flow develops in a laminar manner, meaning without the presence of turbulence.

ID:(2218, 0)

Laminars in the stream

Concept

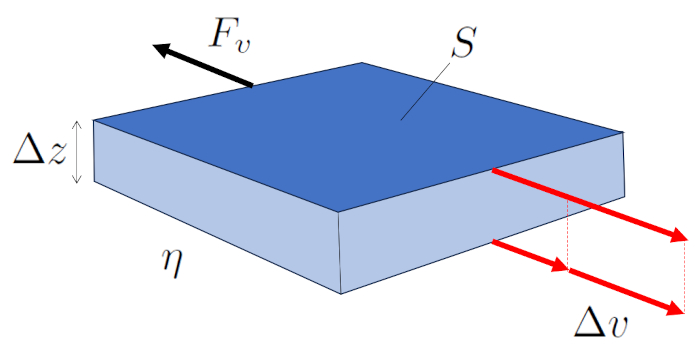

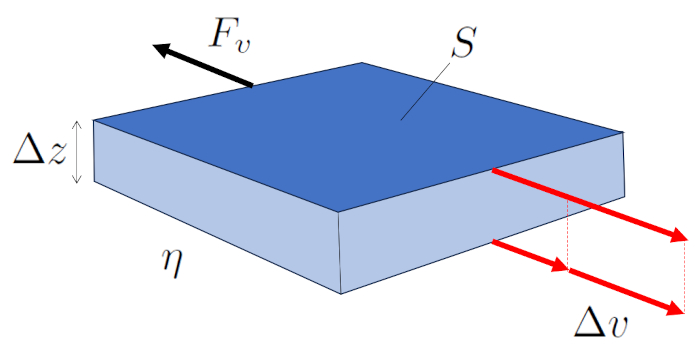

In laminar flow, adjacent layers move, and there exists a force generated by viscosity between them. The faster layer drags its slower neighbor, while the slower one restricts the advancement of the faster one.

Therefore, the force the viscose force ($F_v$) generated by ERROR:10119.1 over the other is a function of ERROR:5556.1, ERROR:5436.1, and ERROR:5422.1, as depicted in the following equation:

| $ F_v =- S \eta \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta v }{ \Delta z }$ |

illustrated in the following diagram:

ID:(7053, 0)

Flow through a cylinder

Concept

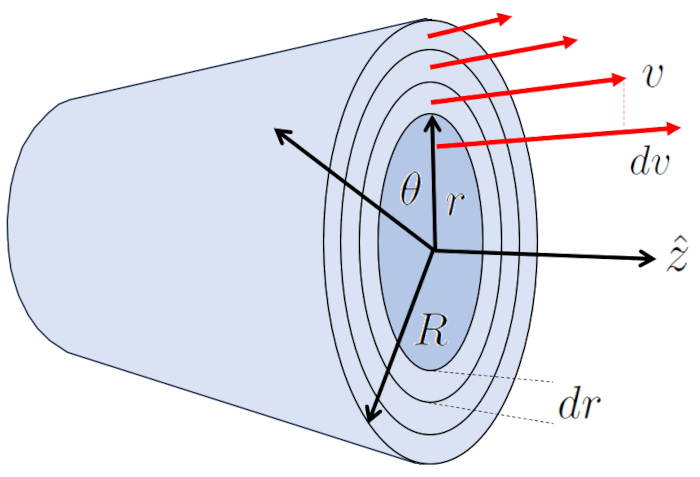

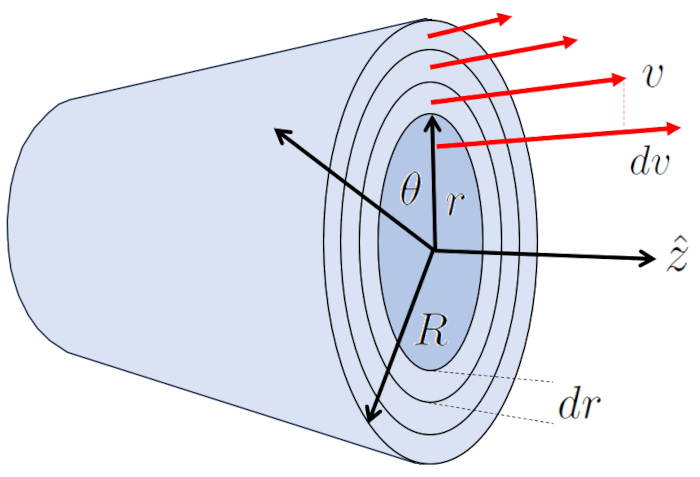

Laminar flow around a cylinder can be represented as multiple cylindrical layers sliding under the influence of adjacent layers. In this case, the viscose force ($F_v$) with the tube length ($\Delta L$), the viscosity ($\eta$), and the variables the cylinder radial position ($r$) and the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) is expressed as:

| $ F_v =-2 \pi r \Delta L \eta \displaystyle\frac{ dv }{ dr }$ |

The layer at the boundary at ERROR:5417.1 remains stationary due to the boundary effect and, through the viscosity ($\eta$), slows down the adjacent layer which does have velocity.

The center is the part moving at the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$), dragging the surrounding layer. In turn, this layer drags the next one, and so on until reaching the layer in contact with the cylinder wall, which is stationary.

Thus, the system transfers energy from the center to the wall, generating a velocity profile represented by:

| $ v = v_{max} \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{ r ^2}{ R ^2}\right)$ |

with:

| $ v_{max} =-\displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{4 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

ID:(7057, 0)

Flow after Hagen-Poiseuille equation

Concept

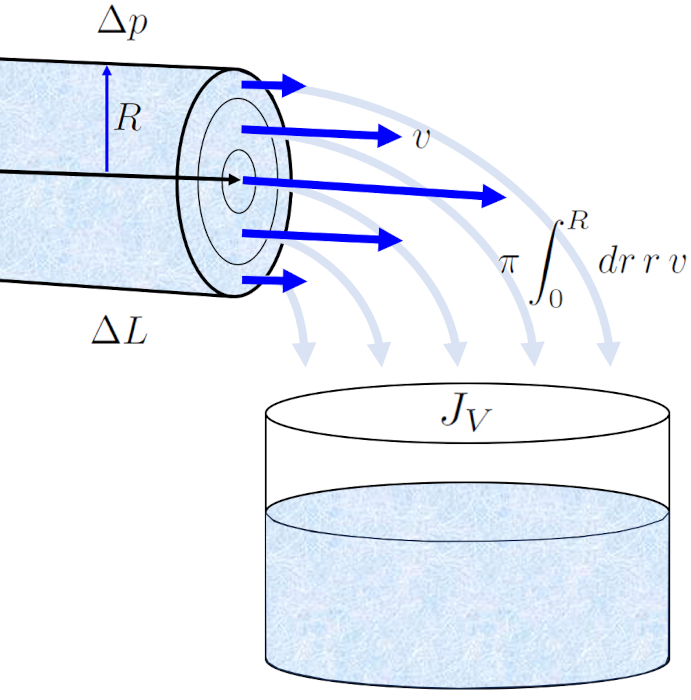

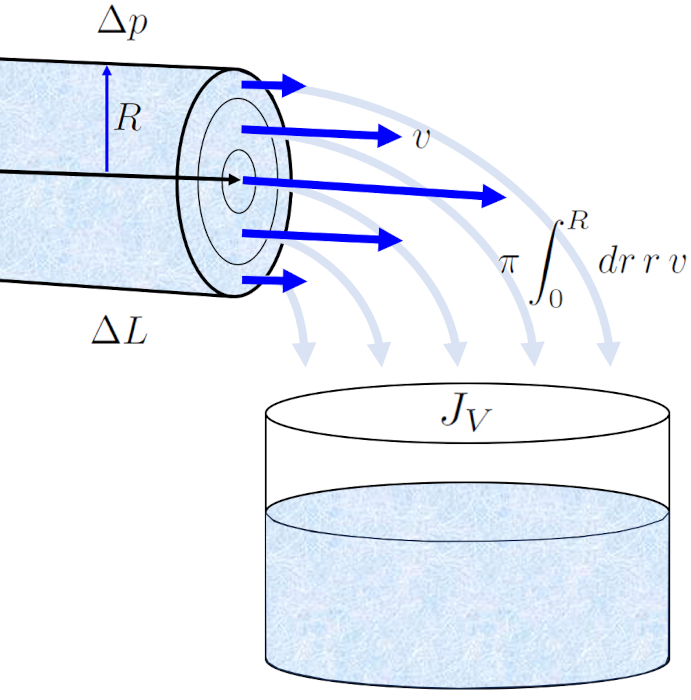

The profile of the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) in the radius of position in a tube ($r$) allows us to calculate the volume flow ($J_V$) in a tube by integrating over the entire surface, which leads us to the well-known Hagen-Poiseuille law.

The result is an equation that depends on ERROR:5417,0 raised to the fourth power. However, it is crucial to note that this flow profile only holds true in the case of laminar flow.

Thus, from the viscosity ($\eta$), it follows that the volume flow ($J_V$) before ERROR:5430.1 and ERROR:6673.1, the expression:

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

The original papers that gave rise to this law with a combined name were:![]() "Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in röhrenförmigen Gefässen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).

"Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in röhrenförmigen Gefässen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).![]() "Recherches expérimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de très-petits diamètres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

"Recherches expérimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de très-petits diamètres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

ID:(2216, 0)

Volume flow

Concept

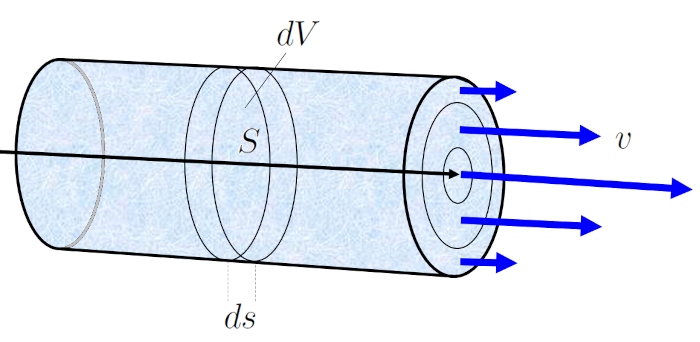

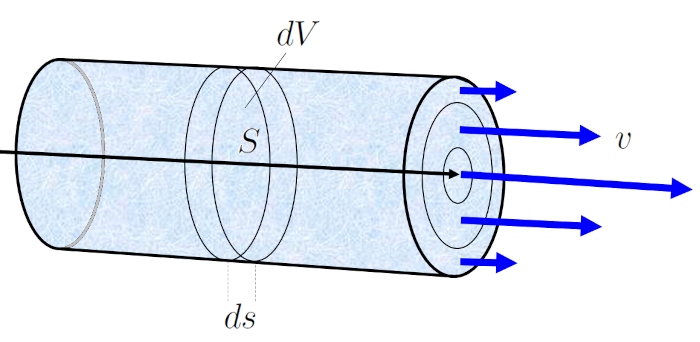

During a time elapsed ($\Delta t$), the fluid with a mean Speed of Fluid ($v$) moves a tube element ($\Delta s$). If the section ($S$) represents the amount of fluid crossing that section in the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), it is calculated as:

$\Delta V = S \Delta s = Sv \Delta t$

This equation states that the volume of fluid flowing through section the section ($S$) during a time elapsed ($\Delta t$) is equal to the product of the cross-sectional area and the distance the fluid travels during that time.

This facilitates the calculation of the volume element ($\Delta V$), which is the volume of fluid flowing through the channel in a specific period of the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), corresponding to the volume flow ($J_V$).

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta V }{ \Delta t }$ |

ID:(2212, 0)

Water Flow

Model

In saturated soil, there can be situations where pressure variations occur. These variations, in turn, generate flow that, in this case, should occur within the soil pores. Since these pores are on the order of microns or tens of microns, the flow tends to be laminar due to the low Reynolds numbers.

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

If we examine the hydraulic conductance ($G_h$), we can notice that the numerator contains the cross-sectional area of the tube, represented as $\pi R^2$. Here, the tube radius ($R$) corresponds to a property of the liquid, the viscosity ($\eta$) is related to the viscosity of the fluid, and the tube length ($\Delta L$) refers to the generated pressure gradient.

| $ G_h =\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta | \Delta L | }$ |

Thus, the factor specific to the geometry of the pores can be defined as the hydrodynamic permeability ($k$) using the following formula:

| $ k = \displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{8}$ |

(ID 108)

If we consider the profile of ERROR:5449,0 for a fluid in a cylindrical channel, where the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) varies with respect to ERROR:10120,0 according to the following expression:

| $ v = v_{max} \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{ r ^2}{ R ^2}\right)$ |

involving the tube radius ($R$) and the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$). We can calculate the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$) using the viscosity ($\eta$), the pressure difference ($\Delta p$), and the tube length ($\Delta L$) as follows:

| $ v_{max} =-\displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{4 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

If we integrate the velocity across the cross-section of the channel, we obtain the volume flow ($J_V$), defined as the integral of $\pi r v(r)$ with respect to ERROR:10120,0 from $0$ to ERROR:5417,0. This integral can be simplified as follows:

$J_V=-\displaystyle\int_0^Rdr \pi r v(r)=-\displaystyle\frac{R^2}{4\eta}\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta L}\displaystyle\int_0^Rdr \pi r \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{r^2}{R^2}\right)$

The integration yields the resulting Hagen-Poiseuille law:

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

(ID 3178)

The volume flow ($J_V$) can be calculated from the hydraulic conductance ($G_h$) and the pressure difference ($\Delta p$) using the following equation:

| $ J_V = G_h \Delta p $ |

Furthermore, using the relationship for the hydraulic resistance ($R_h$):

| $ R_h = \displaystyle\frac{1}{ G_h }$ |

results in:

| $ \Delta p = R_h J_V $ |

(ID 3179)

As the viscous force is

| $ F_v =- S \eta \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta v }{ \Delta z }$ |

and the surface area of the cylinder is

$S=2\pi R L$

where $R$ is the radius and $L$ is the length of the channel, the viscous force can be expressed as

| $ F_v =-2 \pi r \Delta L \eta \displaystyle\frac{ dv }{ dr }$ |

where $\eta$ represents the viscosity and $dv/dr$ is the velocity gradient between the wall and the flow.

(ID 3623)

When a the pressure difference ($\Delta p_s$) acts on a section with an area of $\pi R^2$, with the tube radius ($R$) as the curvature radio ($r$), it generates a force represented by:

$\pi r^2 \Delta p$

This force drives the liquid against viscous resistance, given by:

| $ F_v =-2 \pi r \Delta L \eta \displaystyle\frac{ dv }{ dr }$ |

By equating these two forces, we obtain:

$\pi r^2 \Delta p = \eta 2\pi r \Delta L \displaystyle\frac{dv}{dr}$

Which leads to the equation:

$\displaystyle\frac{dv}{dr} = \displaystyle\frac{1}{2\eta}\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta L} r$

If we integrate this equation from a position defined by the curvature radio ($r$) to the edge where the tube radius ($R$) (taking into account that the velocity at the edge is zero), we can obtain the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) as a function of the curvature radio ($r$):

| $ v = v_{max} \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{ r ^2}{ R ^2}\right)$ |

Where:

| $ v_{max} =-\displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{4 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

is the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$) at the center of the flow.

(ID 3627)

Since the hydraulic resistance ($R_h$) is equal to the hydraulic conductance ($G_h$) as per the following equation:

| $ R_h = \displaystyle\frac{1}{ G_h }$ |

and since the hydraulic conductance ($G_h$) is expressed in terms of the viscosity ($\eta$), the tube radius ($R$), and the tube length ($\Delta L$) as follows:

| $ G_h =\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta | \Delta L | }$ |

we can conclude that:

| $ R_h =\displaystyle\frac{8 \eta | \Delta L | }{ \pi R ^4}$ |

(ID 3629)

(ID 3804)

Flow is defined as the volume the volume element ($\Delta V$) divided by time the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), which is expressed in the following equation:

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta V }{ \Delta t }$ |

and the volume equals the cross-sectional area the section Tube ($S$) multiplied by the distance traveled the tube element ($\Delta s$):

| $ \Delta V = S \Delta s $ |

Since the distance traveled the tube element ($\Delta s$) per unit time the time elapsed ($\Delta t$) corresponds to the velocity, it is represented by:

| $ j_s =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta s }{ \Delta t }$ |

Thus, the flow is a flux density ($j_s$), which is calculated using:

| $ j_s = \displaystyle\frac{ J_V }{ S }$ |

(ID 4349)

The definition of the volume flow ($J_V$) is the volume element ($\Delta V$) over the time elapsed ($\Delta t$):

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta V }{ \Delta t }$ |

which, in the limit of an infinitesimal time interval, corresponds to the derivative of the volume ($V$) with respect to the time ($t$):

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ dV }{ dt }$ |

(ID 12713)

(ID 14459)

If we examine the Hagen-Poiseuille law, which allows us to calculate the volume flow ($J_V$) from the tube radius ($R$), the viscosity ($\eta$), the tube length ($\Delta L$), and the pressure difference ($\Delta p$):

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

we can introduce the hydraulic conductance ($G_h$), defined in terms of the tube length ($\Delta L$), the tube radius ($R$), and the viscosity ($\eta$), as follows:

| $ G_h =\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta | \Delta L | }$ |

to arrive at:

| $ J_V = G_h \Delta p $ |

(ID 14471)

Examples

(ID 15202)

The solution obtained for the height and the parameters the flow at a reference point ($j_{s0}$) and the reference height of the water column ($h_0$) shows us that the flux density ($j_s$) is equal to:

| $ \displaystyle\frac{ j_s }{ j_{s0} } = \displaystyle\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \displaystyle\frac{ 2 x }{ s_0 }}} $ |

We can graphically represent the flux density ($j_s$) in terms of the additional factors $j_s/j_{s0}$ and $x/x_0$ as follows:

the flux density ($j_s$) continues to increase as we approach the channel, as the height of the water column on the ground ($h$) decreases. This increase is necessary to maintain the flow velocity in the flux density ($j_s$) or, alternatively, to increase it.

(ID 7827)

When a tube filled with liquid with a viscosity of ERROR:5422,0 is exposed to the pressure in the initial position ($p_i$) at the position at the beginning of the tube ($L_i$) and the pressure in end position (e) ($p_e$) at the position at the end of the tube ($L_e$), it generates a pressure difference ($\Delta p_s$) along the tube length ($\Delta L$), resulting in the profile of the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$):

In flows with low values of the number of Reynold ($Re$), where viscosity is more significant than the inertia of the liquid, the flow develops in a laminar manner, meaning without the presence of turbulence.

(ID 2218)

In laminar flow, adjacent layers move, and there exists a force generated by viscosity between them. The faster layer drags its slower neighbor, while the slower one restricts the advancement of the faster one.

Therefore, the force the viscose force ($F_v$) generated by ERROR:10119.1 over the other is a function of ERROR:5556.1, ERROR:5436.1, and ERROR:5422.1, as depicted in the following equation:

| $ F_v =- S \eta \displaystyle\frac{ \Delta v }{ \Delta z }$ |

illustrated in the following diagram:

(ID 7053)

Laminar flow around a cylinder can be represented as multiple cylindrical layers sliding under the influence of adjacent layers. In this case, the viscose force ($F_v$) with the tube length ($\Delta L$), the viscosity ($\eta$), and the variables the cylinder radial position ($r$) and the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) is expressed as:

| $ F_v =-2 \pi r \Delta L \eta \displaystyle\frac{ dv }{ dr }$ |

The layer at the boundary at ERROR:5417.1 remains stationary due to the boundary effect and, through the viscosity ($\eta$), slows down the adjacent layer which does have velocity.

The center is the part moving at the maximum flow rate ($v_{max}$), dragging the surrounding layer. In turn, this layer drags the next one, and so on until reaching the layer in contact with the cylinder wall, which is stationary.

Thus, the system transfers energy from the center to the wall, generating a velocity profile represented by:

| $ v = v_{max} \left(1-\displaystyle\frac{ r ^2}{ R ^2}\right)$ |

with:

| $ v_{max} =-\displaystyle\frac{ R ^2}{4 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

(ID 7057)

The profile of the speed on a cylinder radio ($v$) in the radius of position in a tube ($r$) allows us to calculate the volume flow ($J_V$) in a tube by integrating over the entire surface, which leads us to the well-known Hagen-Poiseuille law.

The result is an equation that depends on ERROR:5417,0 raised to the fourth power. However, it is crucial to note that this flow profile only holds true in the case of laminar flow.

Thus, from the viscosity ($\eta$), it follows that the volume flow ($J_V$) before ERROR:5430.1 and ERROR:6673.1, the expression:

| $ J_V =-\displaystyle\frac{ \pi R ^4}{8 \eta }\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta p }{ \Delta L }$ |

The original papers that gave rise to this law with a combined name were:![]() "Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in r hrenf rmigen Gef ssen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).

"Ueber die Gesetze, welche des der Strom des Wassers in r hrenf rmigen Gef ssen bestimmen" (On the laws governing the flow of water in cylindrical vessels), Gotthilf Hagen, Annalen der Physik und Chemie 46:423442 (1839).![]() "Recherches exp rimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de tr s-petits diam tres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Acad mie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

"Recherches exp rimentales sur le mouvement des liquides dans les tubes de tr s-petits diam tres" (Experimental research on the movement of liquids in tubes of very small diameters), Jean-Louis-Marie Poiseuille, Comptes Rendus de l'Acad mie des Sciences 9:433544 (1840).

(ID 2216)

During a time elapsed ($\Delta t$), the fluid with a mean Speed of Fluid ($v$) moves a tube element ($\Delta s$). If the section ($S$) represents the amount of fluid crossing that section in the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), it is calculated as:

$\Delta V = S \Delta s = Sv \Delta t$

This equation states that the volume of fluid flowing through section the section ($S$) during a time elapsed ($\Delta t$) is equal to the product of the cross-sectional area and the distance the fluid travels during that time.

This facilitates the calculation of the volume element ($\Delta V$), which is the volume of fluid flowing through the channel in a specific period of the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), corresponding to the volume flow ($J_V$).

| $ J_V =\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta V }{ \Delta t }$ |

(ID 2212)

(ID 15221)

ID:(369, 0)