Newton's Laws for the Rotation

Definition

Due to the relationship between force and torque, it becomes possible to formulate the laws of rotation based on Newton's principles. Therefore, a connection should exist between the following concepts:

Principle 1

A constant moment > corresponds to a constant angular momentum.

Principle 2

A force: Change in momentum over time > corresponds to a torque: Change in angular momentum over time.

Principle 3

A reaction force > corresponds to a reaction torque.

ID:(1073, 0)

Rotation Generation

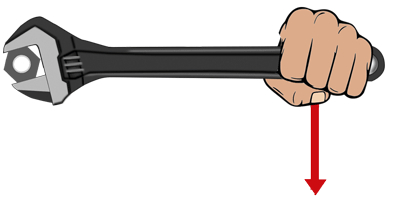

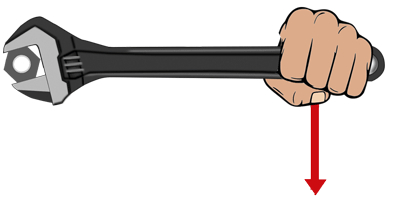

Image

Up until now, we have explored how force results in translation, but we haven't yet delved into how rotation is generated.

From the previous discussion, it can be concluded that any force $\vec{F}$ can be decomposed into two components. The first component, $\vec{F}{\parallel}$, lies along the line connecting the point of application (PA) to the center of mass (CM) of the object. The second component is $\vec{F}{\perp}$, which is perpendicular to the line connecting the point of application to the center of mass.

The first component causes the translation of the object, while the second component gives rise to its rotation.

ID:(322, 0)

Center of mass (CM) concept

Note

If one considers the distribution of mass in space, it should always be possible to identify a point where the force exerted by the mass on one side is equal to the force generated on the other side:

This concept implies that for any orientation of an object, a point of support can be located, at which the object is in balance. Each of these points corresponds to a vertical line. By repeating this process with different orientations of the object, it eventually becomes evident that the vertical lines intersect at a particular point within the object. This point is referred to as the center of mass (CM). In essence, the center of mass is the unique point within the object where, regardless of its orientation, equilibrium is always achieved.

ID:(323, 0)

Force and Torque

Quote

As we have seen, torque plays a role analogous to force in the case of rotation:

$F\longleftrightarrow T$

To establish the equations of motion, we can recall how force was defined in terms of momentum:

$F=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t}$

and how torque was defined:

$T=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta L}{\Delta t}$

We can establish a relationship between the two to describe the generation of torque based on force:

Hence, we must first define what the equivalent of Momentum is in the context of rotation.

ID:(325, 0)

Caso de Rotación

Storyboard

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

If we have multiple masses $m_i$, each one will experience a gravitational force

generating a torque equal to

where $r_i$ is the horizontal distance from mass $i$ to the pivot point. The total torque will be

$T=\displaystyle\sum_iT_i$

If $r_{CM}$ is the position of the center of mass, the total torque around this point

$T_{CM}=\displaystyle\sum_i T_i=\displaystyle\sum_i(r_i-r_{CM})m_ig=0$

must be zero. From this equation, we can solve for the center of mass position, resulting in

As the magnitude of torque is

If the axis unit vector is

$\hat{n}=\hat{r}\times\hat{t}$

Therefore, considering

$\vec{F} =F\hat{t}$

,

$\vec{r} =r\hat{r}$

,

$\vec{T}=T\hat{n}$

we have

$\vec{T} =T\hat{n}=T\hat{r}\times\hat{t}=rF\hat{r}\times\hat{t}=\vec{r}\times\vec{F}$

which means

In the case of a balance, a gravitational force acts on each arm, generating a torque

If the lengths of the arms are $d_i$ and the forces are $F_i$ with $i=1,2$, the equilibrium condition requires that the sum of the torques be zero:

Therefore, considering that the sign of each torque depends on the direction in which it induces rotation,

$d_1F_1-d_2F_2=0$

which results in

Con la definici n de torque medio:

$T\equiv \lim_{t\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{\Delta L}{\Delta t}\equiv \displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}$

con lo que el torque instantaneo se define con la derivada del momento angular:

Since the moment is equal to

it follows that in the case where the moment of inertia doesn't change with time,

$T=\displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}=\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(I\omega) = I\displaystyle\frac{d\omega}{dt} = I\alpha$

which implies that

Si se deriva en el tiempo la relaci n para el momento angular

para el caso de que el radio sea constante

$T=\displaystyle\frac{dL}{dt}=r\displaystyle\frac{dp}{dt}=rF$

por lo que

Para calcular el momento de inercia de un cuerpo se debe considerar este desglosado en peque os vol menes que se suman para obtener el momento de inercia total

Como los momentos de inercia de masas

$I=\displaystyle\sum_k I_k =\displaystyle\sum_k m_k r_k^2 = \displaystyle\sum_k \rho r_k^2 dV \rightarrow \displaystyle\int_V \rho r^2 dV$

por lo que

Examples

Due to the relationship between force and torque, it becomes possible to formulate the laws of rotation based on Newton's principles. Therefore, a connection should exist between the following concepts:

Principle 1

A constant moment > corresponds to a constant angular momentum.

Principle 2

A force: Change in momentum over time > corresponds to a torque: Change in angular momentum over time.

Principle 3

A reaction force > corresponds to a reaction torque.

So far, we have examined how force generates translation, but we have not yet analyzed how rotation occurs.

From the previous discussion, it follows that any force $\vec{F}$ can be decomposed into two components. The first, $\vec{F}{\parallel}$, lies along the line that connects the point of application (PA) to the center of mass (CM) of the body. The second component, $\vec{F}{\perp}$, is perpendicular to the line joining the point of application to the center of mass.

The first component generates the translation of the body, while the second component is responsible for its rotation.

The moment ($p$) was defined as the product of the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$), which is equal to:

The analogue of the speed ($v$) in the case of rotation is the instantaneous Angular Speed ($\omega$), therefore, the equivalent of the moment ($p$) should be a the angular Momentum ($L$) of the form:

the inertial Mass ($m_i$) is associated with the inertia in the translation of a body, so the moment of Inertia ($I$) corresponds to the inertia in the rotation of a body.

Similar to the relationship that exists between linear velocity and angular velocity, represented by the equation:

we can establish a relationship between angular momentum and translational momentum. However, in this instance, the multiplying factor is not the radius, but rather the moment. The relationship is expressed as:

El torque medio calculado con la variaci n del momento angular

por ello el torque instantaneo se puede definir en el limite de tiempo infinitesimal:

Si el eje no varia y la distribuci n de la masa no varia el momento de inercia es constante se tiene que es

In the case where the moment of inertia is constant, the derivative of angular momentum is equal to

which implies that the torque is equal to

This relationship is the equivalent of Newton's second law for rotation instead of translation.

Si el torque es nulo y se cumple el segundo principio que es igual a

el momento de angular se mantiene constante es

Si el momento angular se mantiene constante

se tiene con

se tiene que variaciones en el momento de inercia es compensado con variaciones en la velocidad angular

Both the first and second laws of Newton apply to rotational motion.

Inertia explains that objects tend to maintain a constant angular velocity while rotating.

Changes in angular momentum over time are associated with torque, which, analogous to force in translation, is what causes rotation.

In the case of the third principle, which associates every action with an equal and opposite reaction:

in a similar manner, for every applied torque $T_a$ there exists a reaction torque $T_r$ of equal magnitude but opposite direction:

This physically implies that we always need a pivot point to generate torque so that the system can experience the reaction torque.

If one considers the distribution of mass in space, it should always be possible to identify a point where the force exerted by the mass on one side is equal to the force generated on the other side:

This concept implies that for any orientation of an object, a point of support can be located, at which the object is in balance. Each of these points corresponds to a vertical line. By repeating this process with different orientations of the object, it eventually becomes evident that the vertical lines intersect at a particular point within the object. This point is referred to as the center of mass (CM). In essence, the center of mass is the unique point within the object where, regardless of its orientation, equilibrium is always achieved.

If a bar mounted on a point acting as a pivot is subjected to the force 1 ($F_1$) at the force - axis distance (arm) 1 ($d_1$) from the pivot, generating a torque $T_1$, and to the force 2 ($F_2$) at the force - axis distance (arm) 2 ($d_2$) from the pivot, generating a torque $T_2$, it will be in equilibrium if both torques are equal. Therefore, the equilibrium corresponds to the so-called law of the lever, expressed as:

When a body is in rotational equilibrium, it does not rotate around its center of mass. To achieve this, the sum of the torques acting on it must be zero. This implies that:

Since the relationship between angular momentum and torque is

its temporal derivative leads us to the torque relationship

The body's rotation occurs around an axis in the direction of the torque, which passes through the center of mass.

As we have seen, torque plays a role analogous to force in the case of rotation:

$F\longleftrightarrow T$

To establish the equations of motion, we can recall how force was defined in terms of momentum:

$F=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t}$

and how torque was defined:

$T=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta L}{\Delta t}$

We can establish a relationship between the two to describe the generation of torque based on force:

Hence, we must first define what the equivalent of Momentum is in the context of rotation.

Torque is represented as a vector aligned with the axis of rotation. Because the radius of rotation and the force are orthogonal, the relationship is

This can be expressed as the cross product of angular velocity and radius:

Upon observing an object that is supported from a point, we notice the need to carefully balance it to prevent it from rolling in either direction. This leads us to the concept of finding a point from which the body can be balanced without any rotation.

This point is referred to as the center of mass.

To determine the equilibrium point, we can balance the object along each of its axes. By orienting it in a certain way and finding the position where it remains balanced, we identify an imaginary line upon which the center of mass lies.

Once one of the coordinates of the center of mass has been determined, the object is rotated to find the next coordinate of the center of mass.

In this manner, a point known as the center of mass is determined, and it can be calculated using:

ID:(677, 0)