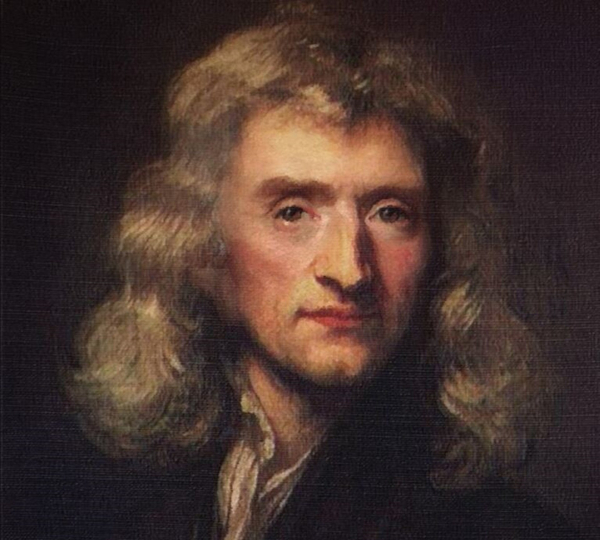

Isaac Newton

Definition

Newton was the first to establish the basic principles that enable us to understand motion. His work, "Principia Mathematica," summarizes three fundamental laws that allow us to calculate how bodies move.

The foundation of his thinking lies in the concept of change in momentum over time, which he refers to as force. In the absence of force, momentum remains constant, resulting in an unaltered velocity when mass is constant. Additionally, Newton conceived the idea that forces occur in pairs; for a force to exist, its opposite reaction must also exist. These principles, known as Newton\'s laws of motion, laid the groundwork for classical physics and remain essential for understanding the behavior of objects in motion.

ID:(636, 0)

Constant mass

Image

Una situación especial es cuando la masa es constante o sea no varia, por lo que es:

|

|

ID:(10581, 0)

Theory

Storyboard

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

The momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$) can be expressed as a set of its different components:

$\vec{p}=(p_x,p_y,p_z)$

Its derivative can be expressed as the derivative of each of its components, so with:

we obtain, by differentiating with respect to the time ($t$), that

$\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}\vec{p}=\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(p_x,p_y,p_z)=\left(\displaystyle\frac{dp_x}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dp_y}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dp_z}{dt}\right)=(F_x,F_y,F_z)=\vec{F}$

which allows us to determine the force ($\vec{F}$):

As the relationship with the action force ($F_A$) and the reaction force ($F_R$) in one dimension is

it can be applied to each component of the action force (vector) ($\vec{F}_A$) and the reaction force (vector) ($\vec{F}_R$), resulting in

$\vec{F}R=(F{Rx},F_{Ry},F_{Rz})=(-F_{Ax},-F_{Ay},-F_{Az})=-\vec{F}_A$

hence

As a vector can be expressed as an array of its different components

$\vec{a}=(a_x,a_y,a_z)$

its derivative can be expressed as the derivative of each of its components

$m_i\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}\vec{a}=m_i\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(a_x,a_y,a_z)=\left(m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_x}{dt},m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_y}{dt},m_i\displaystyle\frac{da_z}{dt}\right)=(F_x,F_y,F_z)=\vec{F}$

Therefore, in general, the instantaneous velocity in more than one dimension is

If the moment ($p$) is defined with the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$) as

This relationship can be generalized for more than one dimension. In this sense, if we define the vector of the velocidad de las partículas (vector) ($\vec{v}$) and the momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$) as

$\vec{p}=(p_x,p_y,p_z)=(m_iv_x,m_iv_y,m_iv_z)=m_i(v_x,v_y,v_z)=m_i\vec{v}$

then

If we consider the variation of momentum over time $t+\Delta t$ and at $t$ as:

$\Delta p = p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)$

and $\Delta t$ as the elapsed time, then in the limit of infinitesimally small time intervals:

$F_m=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta p}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)}{\Delta t}\rightarrow \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{p(t+\Delta t)-p(t)}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{dp}{dt}$

This last expression corresponds to the derivative of the position function $p(t)$:

which is also the slope of the graph representing that function over time.

Examples

Newton was the first to establish the basic principles that enable us to understand motion. His work, "Principia Mathematica," summarizes three fundamental laws that allow us to calculate how bodies move.

The foundation of his thinking lies in the concept of change in momentum over time, which he refers to as force. In the absence of force, momentum remains constant, resulting in an unaltered velocity when mass is constant. Additionally, Newton conceived the idea that forces occur in pairs; for a force to exist, its opposite reaction must also exist. These principles, known as Newton\'s laws of motion, laid the groundwork for classical physics and remain essential for understanding the behavior of objects in motion.

Momentum is a measure of the quantity of motion that increases with both mass and velocity.

In cases with more dimensions, velocity becomes a vector and thus so does momentum:

According to Galileo, objects tend to maintain their state of motion, meaning that the momentum

$\vec{p} = m\vec{v}$

should remain constant. If there is any action on the system that affects its motion, it will be associated with a change in momentum. The difference between the initial momentum $\vec{p}_0$ and the final momentum $\vec{p}$ can be expressed as:

The force ($F$) is defined as the momentum variation ($\Delta p$) by the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), which is defined by the relationship:

The average force is calculated as the change in momentum $\Delta p$ divided by the elapsed time $\Delta t$, using the formula:

This formula provides an approximation of the real force, which may become distorted if the force fluctuates during the time interval. Therefore, the concept of an instantaneous force is introduced, which is determined over an infinitesimally small time interval.

corresponds to the derivative of momentum and represents the instantaneous force.

In general, the force with constant mass ($F$) should be understood as a three-dimensional vector, that is, the force ($\vec{F}$). This means that the moment ($p$) is described by a vector the momento (vector) ($\vec{p}$). Thus, the expression with the time ($t$):

is generalized as:

It's important to note that the force acts in the direction and sense of the variation of the momentum vector over time.

Una situaci n especial es cuando la masa es constante o sea no varia, por lo que es:

For the case where the inertial Mass ($m_i$) is constant, it also holds true that the force with constant mass ($F$) should be understood as a three-dimensional vector, that is, the force ($\vec{F}$). This implies that the instant acceleration ($a$) is described by a vector the instantaneous acceleration (vector) ($\vec{a}$). Thus, the expression with the force with constant mass ($F$):

is generalized as:

If a body does not change its state, the net force acting on it must be zero, i.e.:

If no force acts on a body, its moment of inertia will remain constant. This means that the product of the inertial Mass ($m_i$) and the speed ($v$) will stay constant. In other words, if the mass increases, the velocity will decrease, and vice versa. To understand why this happens, imagine a cart with a certain mass and velocity to which an additional mass is added. This added mass is initially at rest in our system and therefore has no momentum. The cart must transfer some of its momentum to the new mass so that it acquires the same velocity as the cart, resulting in a loss of momentum and a reduction in the cart's speed:

Conversely, if we throw a mass from a moving cart in such a way that the mass comes to a complete stop, we will recover the momentum that the mass had, thereby increasing the cart's momentum and, consequently, its speed. This can only happen if the mass stops when thrown; if it is simply released, it will continue moving at the same velocity.

This last process also helps us understand the third law of action and reaction, as acting on the released mass allows us to harvest the corresponding reaction.

The relationship between the action force ($F_A$) and the reaction force ($F_R$) in one dimension:

can be generalized to more dimensions with the action force (vector) ($\vec{F}_A$) and the reaction force (vector) ($\vec{F}_R$), as follows:

Cuando un cuerpo esta en equilibrio su centro de masa no se esta desplazando. Para ello la suma de las fuerzas sobre este deben ser nula o sea con

ID:(46, 0)