Gravity with Axis pointing down

Note

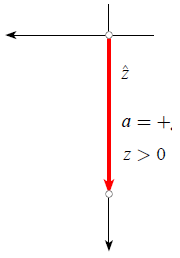

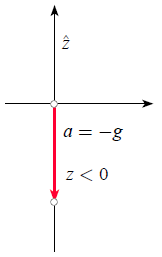

When using a coordinate system with positive z-axis pointing upwards, gravity corresponds to a process of acceleration in the downward direction:

Gravity with axis pointing down

ID:(2249, 0)

Gravity with Axis pointing up

Quote

When using a coordinate system with negative z-axis pointing downwards, gravity corresponds to a process of acceleration in the same direction as the z-axis:

Gravity with axis pointing up

ID:(2250, 0)

Evolution of speed

Exercise

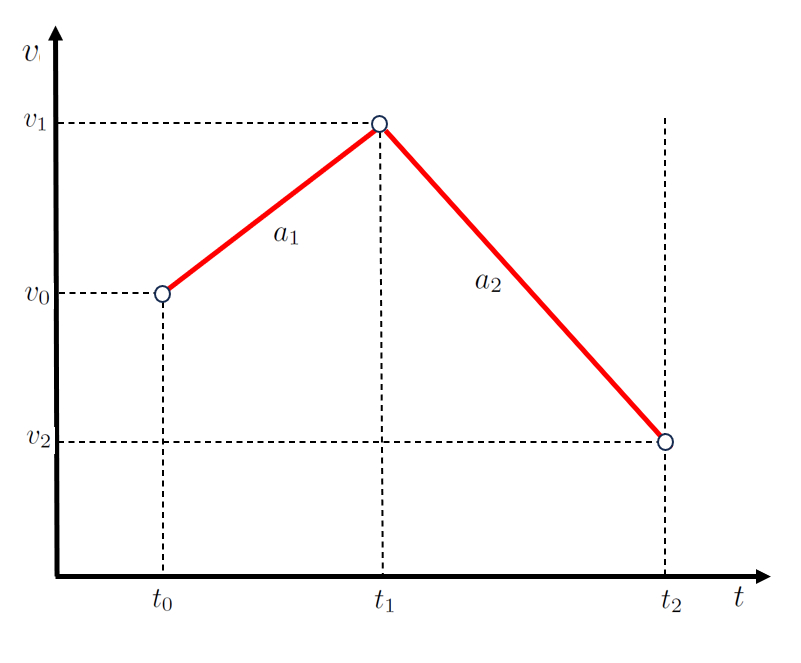

In the case of a two-stage movement, the first stage can be described by a function involving the points the start Time ($t_0$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), and the first stage speed ($v_1$), represented by a line with a slope of the acceleration during the first stage ($a_1$):

| $ v = v_0 + a_0 ( t - t_0 )$ |

For the second stage, defined by the points the first stage speed ($v_1$), the second stage speed ($v_2$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the second stage ending time ($t_2$), a second line with a slope of the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$) is employed:

| $ v = v_0 + a_0 ( t - t_0 )$ |

which is represented as:

ID:(4357, 0)

Tower of Pisa

Equation

It is said that Galileo did his experiments to study gravity by dropping objects from the tower of Pisa:

Tower of Pisa

ID:(2248, 0)

Path traveled as area under speed curve

Script

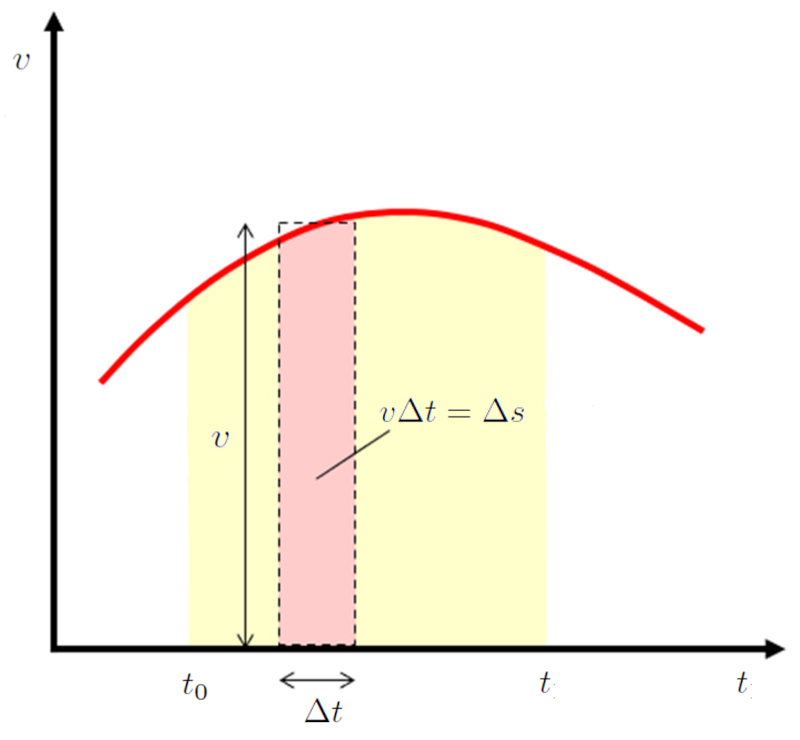

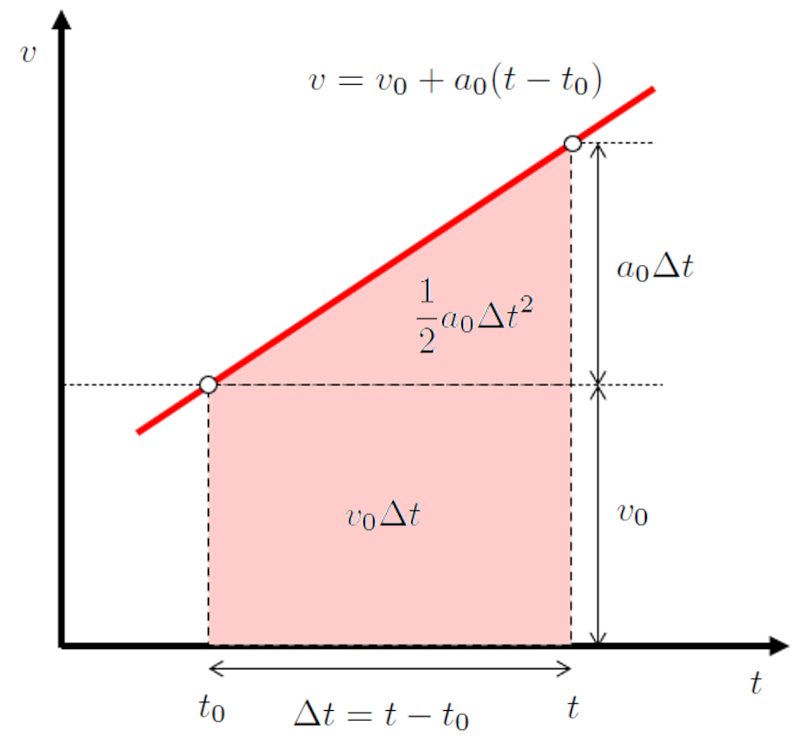

If one observes that the speed ($v$) is equal to the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) per the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), it indicates that the path is given by:

$\Delta s = v\Delta t$

Since the product $v\Delta t$ represents the area under the velocity versus time curve, which is also equal to the traveled path:

This area can also be calculated with the integral of the corresponding function. Therefore, the integral of the acceleration between the start Time ($t_0$) and the time ($t$) corresponds to the change in velocity between the initial velocity the initial Speed ($v_0$) and the speed ($v$):

| $ v = v_0 +\displaystyle\int_{t_0}^t a d\tau $ |

ID:(2252, 0)

Speed in the case of constant acceleration

Variable

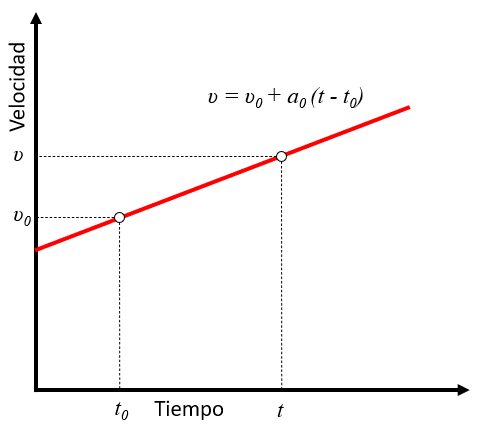

When acceleration is constant, the variation of velocity, represented by the speed ($v$), changes linearly with respect to, the time ($t$). This can be calculated using the initial Speed ($v_0$), the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), and the start Time ($t_0$), giving us the equation:

| $ v = v_0 + a_0 ( t - t_0 )$ |

This relationship is graphically represented as a straight line, as shown below:

ID:(2253, 0)

Evolution of the position

Audio

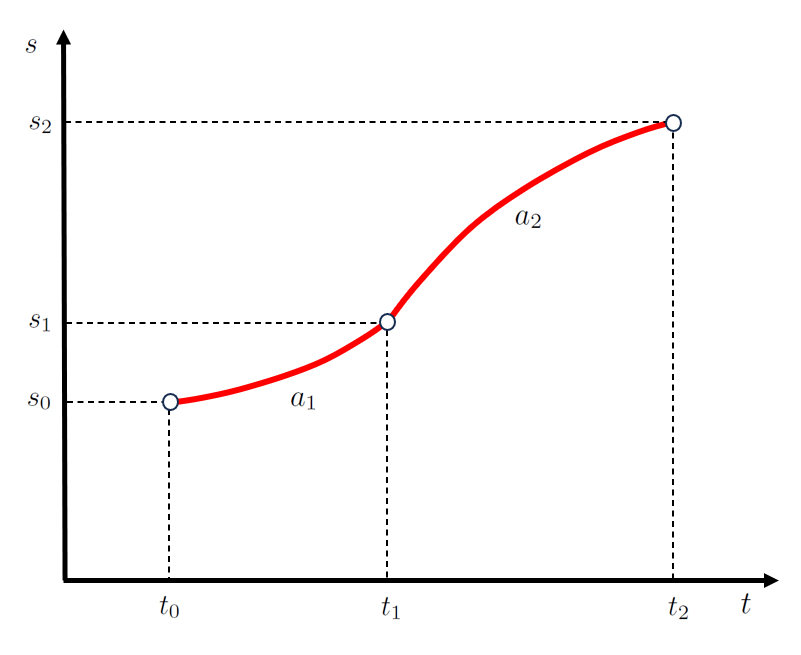

In the case of a two-stage movement, the position at which the first stage ends coincides with the position at the beginning of the second stage ($s_1$).

Similarly, the time at which the first stage ends coincides with the time at the beginning of the second stage ($t_1$).

Since the movement is defined by the acceleration experienced, the velocity attained at the end of the first stage must match the initial velocity of the second stage ($v_1$).

In the case of constant acceleration, in the first stage, the first final position and started second stage ($s_1$) depends on the starting position ($s_0$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), the acceleration during the first stage ($a_1$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the start Time ($t_0$), as follows:

| $ s = s_0 + v_0 ( t - t_0 )+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} a_0 ( t - t_0 )^2$ |

In the second stage, the second stage final position ($s_2$) depends on the first final position and started second stage ($s_1$), the first stage speed ($v_1$), the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the second stage ending time ($t_2$), as follows:

| $ s = s_0 + v_0 ( t - t_0 )+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} a_0 ( t - t_0 )^2$ |

which is represented as:

Area under the constant acceleration curve

ID:(2254, 0)

Calculated path of speed

Video

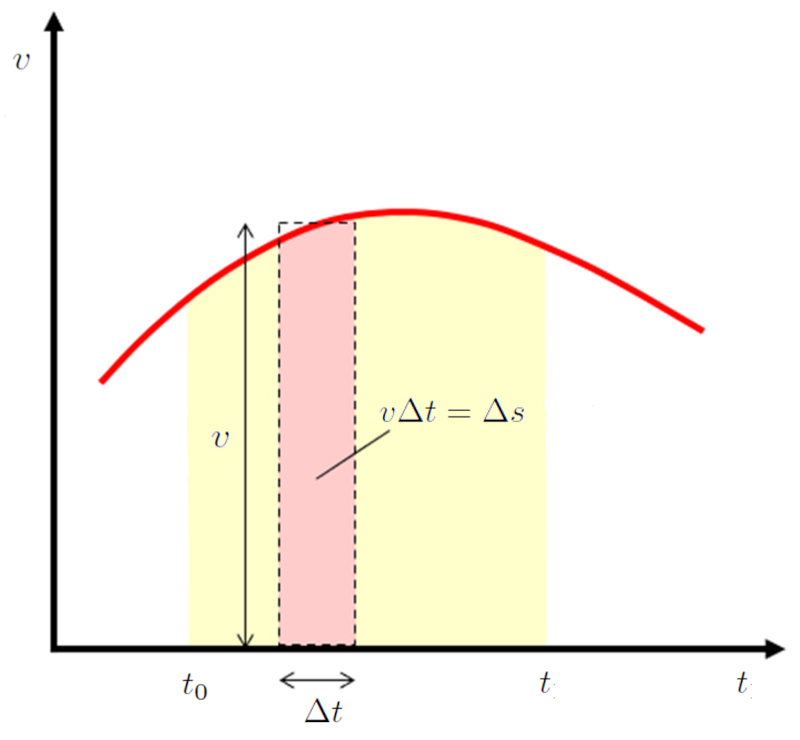

If we consider an area with width $\Delta t$ on a velocity versus time graph, it represents the displacement during that time:

In the particular case where acceleration is constant, velocity is represented on the velocity versus time graph as a straight line. This line is defined by the speed ($v$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), the time ($t$), and the start Time ($t_0$), equal to:

| $ v = v_0 + a_0 ( t - t_0 )$ |

and is graphed as follows:

Since the area under the curve can be represented as the sum of a rectangle with area

$v_0(t-t_0)$

and a triangle with area

$\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}a_0(t-t_0)^2$

We can calculate the displacement the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) from the position ($s$) and the starting position ($s_0$), leading us to:

| $ \Delta s = s_2 - s_1 $ |

Therefore, the position ($s$) is equal to:

| $ s = s_0 + v_0 ( t - t_0 )+\displaystyle\frac{1}{2} a_0 ( t - t_0 )^2$ |

ID:(4828, 0)

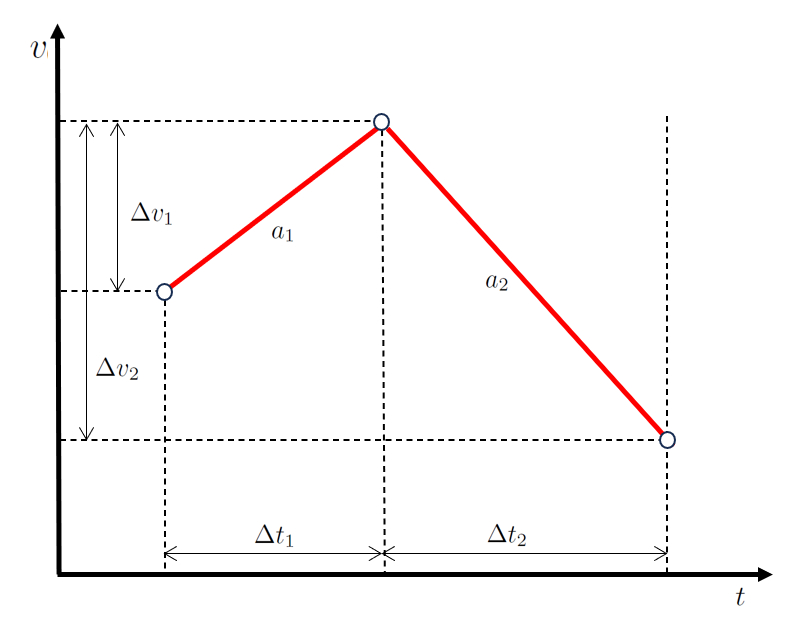

Two-stage movement

Unit

In a scenario of movement in two stages, first the object modifies its velocity by the speed difference in the first stage ($\Delta v_1$) during a time interval of ERROR:10242.1 with an acceleration of ERROR:10260.1.

| $ \bar{a} \equiv\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta v }{ \Delta t }$ |

Subsequently, in the second stage, it progresses by modifying its velocity by the speed difference in the second stage ($\Delta v_2$) during a time interval of the time spent in the second stage ($\Delta t_2$) with an acceleration of the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$).

| $ \bar{a} \equiv\displaystyle\frac{ \Delta v }{ \Delta t }$ |

When represented graphically, we obtain a velocity and time diagram as shown below:

The key here is that the values the time spent in the first stage ($\Delta t_1$) and the time spent in the second stage ($\Delta t_2$) are sequential, just like the values the speed difference in the first stage ($\Delta v_1$) and the speed difference in the second stage ($\Delta v_2$).

ID:(4829, 0)

Human body model

Storyboard

Variables

Calculations

Calculations

Equations

As a vector can be expressed as an array of its different components,

$\vec{v}=(v_x,v_y,v_z)$

its derivative can be expressed as the derivative of each of its components:

$\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}\vec{v}=\displaystyle\frac{d}{dt}(v_x,v_y,v_z)=\left(\displaystyle\frac{dv_x}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dv_y}{dt},\displaystyle\frac{dv_z}{dt}\right)=\displaystyle\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}=\vec{a}$

So, in general, instantaneous velocity in more than one dimension is:

In the case where the constant Acceleration ($a_0$) equals the mean Acceleration ($\bar{a}$), it will be equal to

Therefore, considering the speed Diference ($\Delta v$) as

and the time elapsed ($\Delta t$) as

the equation for the constant Acceleration ($a_0$)

can be written as

$a_0 = \bar{a} = \displaystyle\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} = \displaystyle\frac{v - v_0}{t - t_0}$

and by rearranging, we obtain

In the case of the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), the speed ($v$) as a function of the time ($t$) forms a straight line passing through the start Time ($t_0$) and the initial Speed ($v_0$), defined by the equation:

Since the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) represents the area under the velocity-time curve, we can sum the contributions of the rectangle:

$v_0(t-t_0)$

and the triangle:

$\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}a_0(t-t_0)^2$

To obtain the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) with the position ($s$) and the starting position ($s_0$), resulting in:

Therefore:

If we solve for the time ($t$) and the start Time ($t_0$) in the equation of the speed ($v$), which depends on the initial Speed ($v_0$) and the constant Acceleration ($a_0$):

we get:

$t - t_0= \displaystyle\frac{v - v_0}{a_0}$

And when we substitute this into the equation of the position ($s$) with the starting position ($s_0$):

we obtain an expression for the distance traveled as a function of velocity:

The definition of the mean Acceleration ($\bar{a}$) is considered as the relationship between the speed Diference ($\Delta v$) and the time elapsed ($\Delta t$). That is,

and

The relationship between both is defined as the centrifuge Acceleration ($a_c$)

within this time interval.

If we consider the difference in the speed ($v$) at times $t+\Delta t$ and $t$:

$\Delta v = v(t+\Delta t)-v(t)$

and take $\Delta t$ as the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), then in the limit of infinitesimally short times:

$a=\displaystyle\frac{\Delta v}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{v(t+\Delta t)-v(t)}{\Delta t} \rightarrow \lim_{\Delta t\rightarrow 0}\displaystyle\frac{v(t+\Delta t)-v(t)}{\Delta t}=\displaystyle\frac{dv}{dt}$

This last expression corresponds to the derivative of the function the speed ($v$):

which, in turn, is the slope of the graphical representation of that function at the time ($t$).

En el caso de que se asuma que el tiempo inicial es nulo\\n\\n

$t_0=0$

la ecuaci n de la posici n

se reduce a

Examples

The sum of road intervals corresponds to the sum of the

How the distance

it has to

Acceleration corresponds to the change in velocity per unit of time.

Therefore, it is necessary to define the speed Diference ($\Delta v$) in terms of the speed ($v$) and the initial Speed ($v_0$) as follows:

If an object is described in a coordinate system where the z-axis points \"down\" (towards the ground), the acceleration it experiences is equal to the gravitational acceleration, which is defined as positive:

$a = g > 0$

Since the acceleration is constant, the velocity will evolve linearly, as shown in the following equation:

Therefore, in this case, it can be reduced to the following equation:

When using a coordinate system with positive z-axis pointing upwards, gravity corresponds to a process of acceleration in the downward direction:

When using a coordinate system with negative z-axis pointing downwards, gravity corresponds to a process of acceleration in the same direction as the z-axis:

If an object is described in a coordinate system where the z-axis points upwards (towards the sky), the acceleration experienced by the object is equal to the gravitational acceleration defined as negative, given by

$a = -g < 0$

.

Since the acceleration is constant, the velocity of the object will change linearly, as described by the equation

which simplifies to

in this particular case.

In the case of a two-stage movement, the first stage can be described by a function involving the points the start Time ($t_0$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), and the first stage speed ($v_1$), represented by a line with a slope of the acceleration during the first stage ($a_1$):

For the second stage, defined by the points the first stage speed ($v_1$), the second stage speed ($v_2$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the second stage ending time ($t_2$), a second line with a slope of the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$) is employed:

which is represented as:

In general, velocity should be understood as a three-dimensional vector. That is to say, its the position ($s$) needs to be described by a vector a posición (vector) ($\vec{s}$), for which each component the speed ($v$) can be defined as shown in the following equation:

This allows for the generalization of the speed (Vector) ($\vec{v}$) as follows:

If the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), then the mean Acceleration ($\bar{a}$) is equal to the value of acceleration, that is,

In this case, the speed ($v$) as a function of the time ($t$) can be calculated by considering that it is associated with the difference between the speed ($v$) and the initial Speed ($v_0$), as well as the time ($t$) and the start Time ($t_0$).

This equation thus represents a straight line in velocity-time space.

It is said that Galileo did his experiments to study gravity by dropping objects from the tower of Pisa:

The proportion in which the variation of velocity over time is defined as the mean Acceleration ($\bar{a}$). To measure it, it is necessary to observe the speed Diference ($\Delta v$) and the time elapsed ($\Delta t$).

One common method for measuring average acceleration involves using a stroboscopic lamp that illuminates the object at defined intervals. By taking a photograph, one can determine the distance traveled by the object in that time. By calculating two consecutive velocities, one can determine their variation and, with the time elapsed between the photos, the average acceleration.

The equation that describes average acceleration is as follows:

It is important to note that average acceleration is an estimation of actual acceleration.

The main problem is that if acceleration varies during the elapsed time, the value of the average acceleration may differ greatly from the mean acceleration

.

Therefore, the key is to

Determine acceleration over a sufficiently short period of time to minimize variation.

The variable the mean Acceleration ($\bar{a}$), calculated as the change in the speed Diference ($\Delta v$) divided by the interval of the time elapsed ($\Delta t$) through

is an approximation of the actual acceleration, which tends to distort when the acceleration fluctuates during the time interval. Therefore, the concept of the instant acceleration ($a$) determined over a very small time interval is introduced. In this case, we are referring to an infinitesimally small time interval, and the variation of velocity over time reduces to the derivative of the speed ($v$) with respect to the time ($t$):

which corresponds to the derivative of velocity.

If one observes that the speed ($v$) is equal to the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) per the time elapsed ($\Delta t$), it indicates that the path is given by:

$\Delta s = v\Delta t$

Since the product $v\Delta t$ represents the area under the velocity versus time curve, which is also equal to the traveled path:

This area can also be calculated with the integral of the corresponding function. Therefore, the integral of the acceleration between the start Time ($t_0$) and the time ($t$) corresponds to the change in velocity between the initial velocity the initial Speed ($v_0$) and the speed ($v$):

When acceleration is constant, the variation of velocity, represented by the speed ($v$), changes linearly with respect to, the time ($t$). This can be calculated using the initial Speed ($v_0$), the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), and the start Time ($t_0$), giving us the equation:

This relationship is graphically represented as a straight line, as shown below:

In the case of a two-stage movement, the position at which the first stage ends coincides with the position at the beginning of the second stage ($s_1$).

Similarly, the time at which the first stage ends coincides with the time at the beginning of the second stage ($t_1$).

Since the movement is defined by the acceleration experienced, the velocity attained at the end of the first stage must match the initial velocity of the second stage ($v_1$).

In the case of constant acceleration, in the first stage, the first final position and started second stage ($s_1$) depends on the starting position ($s_0$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), the acceleration during the first stage ($a_1$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the start Time ($t_0$), as follows:

In the second stage, the second stage final position ($s_2$) depends on the first final position and started second stage ($s_1$), the first stage speed ($v_1$), the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$), the final time of first and start of second stage ($t_1$), and the second stage ending time ($t_2$), as follows:

which is represented as:

In the case of ERROR:5297.1, the speed ($v$) varies linearly with the time ($t$), using the initial Speed ($v_0$) and the start Time ($t_0$):

Thus, the area under this line can be calculated, yielding the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$). Combining this with the starting position ($s_0$), we can calculate the position ($s$), resulting in:

This corresponds to the general form of a parabola.

En el caso de que se asuma que la aceleraci n inicial es constante y tiempo inicial nulo la ecuaci n de la posici n

se reduce a

If we consider an area with width $\Delta t$ on a velocity versus time graph, it represents the displacement during that time:

In the particular case where acceleration is constant, velocity is represented on the velocity versus time graph as a straight line. This line is defined by the speed ($v$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), the constant Acceleration ($a_0$), the time ($t$), and the start Time ($t_0$), equal to:

and is graphed as follows:

Since the area under the curve can be represented as the sum of a rectangle with area

$v_0(t-t_0)$

and a triangle with area

$\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}a_0(t-t_0)^2$

We can calculate the displacement the distance traveled in a time ($\Delta s$) from the position ($s$) and the starting position ($s_0$), leading us to:

Therefore, the position ($s$) is equal to:

In the case of constant acceleration, we can calculate the position ($s$) from the starting position ($s_0$), the initial Speed ($v_0$), the time ($t$), and the start Time ($t_0$) using the equation:

This allows us to determine the relationship between the distance covered during acceleration/deceleration and the change in velocity:

In a scenario of movement in two stages, first the object modifies its velocity by the speed difference in the first stage ($\Delta v_1$) during a time interval of ERROR:10242.1 with an acceleration of ERROR:10260.1.

Subsequently, in the second stage, it progresses by modifying its velocity by the speed difference in the second stage ($\Delta v_2$) during a time interval of the time spent in the second stage ($\Delta t_2$) with an acceleration of the acceleration during the second stage ($a_2$).

When represented graphically, we obtain a velocity and time diagram as shown below:

The key here is that the values the time spent in the first stage ($\Delta t_1$) and the time spent in the second stage ($\Delta t_2$) are sequential, just like the values the speed difference in the first stage ($\Delta v_1$) and the speed difference in the second stage ($\Delta v_2$).

ID:(36, 0)